If you don’t get seasick, an autonomous boat might be the right mode of transportation for you.

Scientists from MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL) and the Senseable City Laboratory, together with Amsterdam Institute for Advanced Metropolitan Solutions (AMS Institute) in the Netherlands, have now created the final project in their self-navigating trilogy: a full-scale, fully autonomous robotic boat that’s ready to be deployed along the canals of Amsterdam.

“Roboat” has come a long way since the team first started prototyping small vessels in the MIT pool in late 2015. Last year, the team released their half-scale, medium model that was 2 meters long and demonstrated promising navigational prowess.

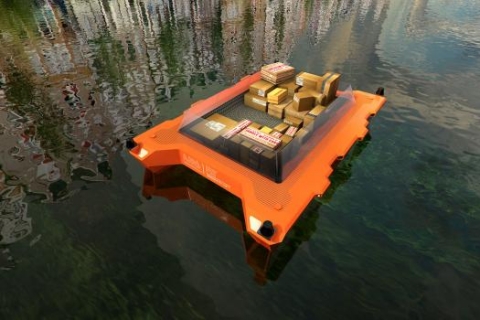

This year, two full-scale Roboats were launched, proving more than just proof-of-concept: these craft can comfortably carry up to five people, collect waste, deliver goods, and provide on-demand infrastructure.

The boat looks futuristic — it’s a sleek combination of black and gray with two seats that face each other, with orange block letters on the sides that illustrate the makers' namesakes. It’s a fully electrical boat with a battery that’s the size of a small chest, enabling up to 10 hours of operation and wireless charging capabilities.

Autonomous Roboats set sea in the Amsterdam canals and can comfortably carry up to five people, collect waste, deliver goods, and provide on-demand infrastructure.

“We now have higher precision and robustness in the perception, navigation, and control systems, including new functions, such as close-proximity approach mode for latching capabilities, and improved dynamic positioning, so the boat can navigate real-world waters,” says Daniela Rus, MIT professor of electrical engineering and computer science and director of CSAIL. “Roboat’s control system is adaptive to the number of people in the boat.”

To swiftly navigate the bustling waters of Amsterdam, Roboat needs a meticulous fusion of proper navigation, perception, and control software.

Using GPS, the boat autonomously decides on a safe route from A to B, while continuously scanning the environment to avoid collisions with objects, such as bridges, pillars, and other boats.

To autonomously determine a free path and avoid crashing into objects, Roboat uses lidar and a number of cameras to enable a 360-degree view. This bundle of sensors is referred to as the “perception kit” and lets Roboat understand its surroundings. When the perception picks up an unseen object, like a canoe, for example, the algorithm flags the item as “unknown.” When the team later looks at the collected data from the day, the object is manually selected and can be tagged as “canoe.”

The control algorithms — similar to ones used for self-driving cars — function a little like a coxswain giving orders to rowers, by translating a given path into instructions toward the “thrusters,” which are the propellers that help the boat move.

If you think the boat feels slightly futuristic, its latching mechanism is one of its most impressive feats: small cameras on the boat guide it to the docking station, or other boats, when they detect specific QR codes. “The system allows Roboat to connect to other boats, and to the docking station, to form temporary bridges to alleviate traffic, as well as floating stages and squares, which wasn’t possible with the last iteration,” says Carlo Ratti, professor of the practice in the MIT Department of Urban Studies and Planning (DUSP) and director of the Senseable City Lab.

Roboat, by design, is also versatile. The team created a universal “hull” design — that’s the part of the boat that rides both in and on top of the water. While regular boats have unique hulls, designed for specific purposes, Roboat has a universal hull design where the base is the same, but the top decks can be switched out depending on the use case.

“As Roboat can perform its tasks 24/7, and without a skipper on board, it adds great value for a city. However, for safety reasons it is questionable if reaching level A autonomy is desirable,” says Fabio Duarte, a principal research scientist in DUSP and lead scientist on the project. “Just like a bridge keeper, an onshore operator will monitor Roboat remotely from a control center. One operator can monitor over 50 Roboat units, ensuring smooth operations.”

The next step for Roboat is to pilot the technology in the public domain. "The historic center of Amsterdam is the perfect place to start, with its capillary network of canals suffering from contemporary challenges, such as mobility and logistics,” says Stephan van Dijk, director of innovation at AMS Institute.

Previous iterations of Roboat have been presented at the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation. The boats will be unveiled on Oct. 28 in the waters of Amsterdam.

Ratti, Rus, Duarte, and Dijk worked on the project alongside Andrew Whittle, MIT’s Edmund K Turner Professor in civil and environmental engineering; Dennis Frenchman, professor at MIT’s Department of Urban Studies and Planning; and Ynse Deinema of AMS Institute. The full team can be found at Roboat's website. The project is a joint collaboration with AMS Institute. The City of Amsterdam is a project partner.