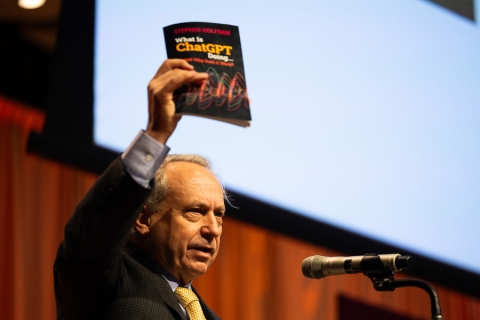

According to some estimates, Google processes roughly 99,000 search queries each second. That means that by the time you’ve read that last sentence, more than every citizen in Atlanta could have searched for cute pictures of cats. During Google Senior Vice President Prabhakar Raghavan’s talk at MIT CSAIL on April 2nd, he explored how modern search engines have reached this scalability and how large language models are impacting their future.

The story of our current search engines began about 30 years ago, according to Raghavan. Back then, classic info retrieval techniques simply found the most relevant documents to match a user’s query. Around the same time, Sir Tim Berners-Lee spearheaded the development of the World Wide Web, which came with a key feature: the lack of a central authority.

This relatively free-spirited approach opened up a can of worms, unsurprisingly. Without an authoritative source telling you which content is legitimate, pages would purport to be authorities on just about everything. As intermediaries, search engines sought to elevate quality sources on a given query. In particular, Google developed page rankings to address this challenge, moving more trustworthy links to the top of searches.

The company observed that users’ satisfaction would vary based on their query, though, since some searches were for direct bits of information and others were more ambiguous. You may look up local pizza shops to get a general idea of what’s nearby, whereas googling the elevation of Machu Picchu warrants a direct answer that’s a consensus of reliable sources. In these cases, users didn’t want to see a simple list of webpages, so Google added more informative features like maps and excerpts that directly answer the query.

Raghavan then detailed how Google now assesses user feedback through human evaluators. These highly trained testers review the relevance of links within searches to help decide when a new ranking algorithm should replace an existing one. With over one million evaluations and live experiments a year, this system helps the company produce more informative search results while carefully toeing the lines of censorship. “We’re trying to deprecate low-quality information, but will not eliminate it. By open-access, we provide a range of information, but we surface high-quality and reliable content,” Raghavan said.

He mentioned that there are some exceptions, like spam and illegal content, which are removed. As for handling misinformation, the Google Senior VP highlighted that they aim “to help users evaluate what they’re looking at” without giving an opinion on the source itself. With breaking news, for example, Google will label results broadly as rapidly changing at the top of results related to that topic.

Next, Raghavan made an acute observation: despite its name, the World Wide Web is not exactly global yet. While two-thirds of humanity uses the Internet, many create content outside of the Web. Apps like TikTok and X — or as he calls them, examples of “walled gardens” — are rapidly growing by allowing users to simply create content and monetize. They are not generally accessible, though, so other creators take a route that isn't growing as fast: the open web, where they can use hosting provider to build a monetizable website.

The other disadvantage of the Web, as it stands, is that 55% of its content is in English, illustrating the lack of content in underserved languages. To demonstrate this flaw, Raghavan showed that while Wikipedia has seven million articles in English, it only has 20,000 entries in the Pashto language native to Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Iran. To translate more articles in underrepresented languages like this, Google is pulling from the simple English Wikipedia. Raghavan’s talk indicated that technical solutions like these can “make the web more worldwide.”

And the language models came marching in

Before his current role at the company, Raghavan grew Gmail and Google Drive past one billion monthly active users with machine intelligence features like smart reply. Implemented around 2015, the predictive feature recommends answers to emails based on the most likely replies.

This adoption of artificial intelligence is one of many for the company. Raghavan mentioned two famous Google papers that opened the door for further advancements: “Attention Is All You Need” and then “BERT.” The former improved the prediction accuracy of language models by proposing a new type of neural network called a transformer to help with searches, which is capable of learning context by tracking relationships in sequential data. The latter paper helped language models understand searches better than before.

These two key papers aided Google in expanding its search results by embedding text, images, and videos together in more helpful ways for users. For instance, if you now search for how to tie a perfect bow, your first result would highlight a specific timestamp within a video to provide a more efficient tutorial. Google’s AI has also led to Google Lens, where a user can do a reverse image search to get to the source of a picture. Earlier this year, the company also launched a new feature that allows users to circle what’s pictured in a video to retrieve results, like identifying a dog’s swimming goggles from a YouTube clip.

Google is also experimenting with Generative AI through its Search Generative Experience. A simple search about “brunch spots near me” may give you a myriad of locations to check out, while their new project can answer more specific prompts like “compare two brunch spots for Vegetarians near me.” In SGE, this leads to a breakdown of two options based on reviews and prices, which is a more synthesized result that shows the promise of AI for search engines that have evolved from the simple information retrieval that was standard thirty years ago.

“I want you to think of a world where this omniscient friend is with you at all times,” envisions Raghavan. To bring that companion to life, Google is toying with multimodal queries that can answer more visual questions, like pointing a camera at a mural and asking who painted it. In a quick demo, the Google VP showed the AI successfully identifying the artist behind the work.

Raghavan concluded his talk by asking a straightforward question: “Even with all the computing cycles in the world, could you build a better search engine?” This open-ended inquiry, he says, drives researchers to keep elevating the user experience and improve algorithmic systems.