So, you need a robot that climbs stairs. What shape should that robot be? Should it have two legs, like a person? Or six, like an ant?

Choosing the right shape will be vital for your robot’s ability to traverse a particular terrain. And it’s impossible to build and test every potential form. But now an MIT-developed system makes it possible to simulate them and determine which design works best.

You start by telling the system, called RoboGrammar, which robot parts are lying around your shop — wheels, joints, etc. You also tell it what terrain your robot will need to navigate. And RoboGrammar does the rest, generating an optimized structure and control program for your robot.

The advance could inject a dose of computer-aided creativity into the field. “Robot design is still a very manual process,” says Allan Zhao, the paper’s lead author and a PhD student in the MIT Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL). He describes RoboGrammar as “a way to come up with new, more inventive robot designs that could potentially be more effective.”

Zhao is the lead author of the paper, which he will present at this month’s SIGGRAPH Asia conference. Co-authors include PhD student Jie Xu, postdoc Mina Konaković-Luković, postdoc Josephine Hughes, PhD student Andrew Spielberg, and professors Daniela Rus and Wojciech Matusik, all of MIT.

Ground rules

Robots are built for a near-endless variety of tasks, yet “they all tend to be very similar in their overall shape and design,” says Zhao. For example, “when you think of building a robot that needs to cross various terrains, you immediately jump to a quadruped,” he adds, referring to a four-legged animal like a dog. “We were wondering if that’s really the optimal design.”

Zhao’s team speculated that more innovative design could improve functionality. So they built a computer model for the task — a system that wasn’t unduly influenced by prior convention. And while inventiveness was the goal, Zhao did have to set some ground rules.

The universe of possible robot forms is “primarily composed of nonsensical designs,” Zhao writes in the paper. “If you can just connect the parts in arbitrary ways, you end up with a jumble,” he says. To avoid that, his team developed a “graph grammar” — a set of constraints on the arrangement of a robot’s components. For example, adjoining leg segments should be connected with a joint, not with another leg segment. Such rules ensure each computer-generated design works, at least at a rudimentary level.

Zhao says the rules of his graph grammar were inspired not by other robots but by animals — arthropods in particular. These invertebrates include insects, spiders, and lobsters. As a group, arthropods are an evolutionary success story, accounting for more than 80 percent of known animal species. “They’re characterized by having a central body with a variable number of segments. Some segments may have legs attached,” says Zhao. “And we noticed that that’s enough to describe not only arthropods but more familiar forms as well,” including quadrupeds. Zhao adopted the arthropod-inspired rules thanks in part to this flexibility, though he did add some mechanical flourishes. For example, he allowed the computer to conjure wheels instead of legs.

A phalanx of robots

Using Zhao’s graph grammar, RoboGrammar operates in three sequential steps: defining the problem, drawing up possible robotic solutions, then selecting the optimal ones. Problem definition largely falls to the human user, who inputs the set of available robotic components, like motors, legs, and connecting segments. “That’s key to making sure the final robots can actually be built in the real world,” says Zhao. The user also specifies the variety of terrain to be traversed, which can include combinations of elements like steps, flat areas, or slippery surfaces.

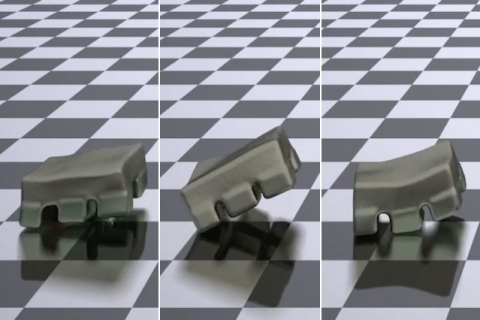

With these inputs, RoboGrammar then uses the rules of the graph grammar to design hundreds of thousands of potential robot structures. Some look vaguely like a racecar. Others look like a spider, or a person doing a push-up. “It was pretty inspiring for us to see the variety of designs,” says Zhao. “It definitely shows the expressiveness of the grammar.” But while the grammar can crank out quantity, its designs aren’t always of optimal quality.

Choosing the best robot design requires controlling each robot’s movements and evaluating its function. “Up until now, these robots are just structures,” says Zhao. The controller is the set of instructions that brings those structures to life, governing the movement sequence of the robot’s various motors. The team developed a controller for each robot with an algorithm called Model Predictive Control, which prioritizes rapid forward movement.

“The shape and the controller of the robot are deeply intertwined,” says Zhao, “which is why we have to optimize a controller for every given robot individually.” Once each simulated robot is free to move about, the researchers seek high-performing robots with a “graph heuristic search.” This neural network algorithm iteratively samples and evaluates sets of robots, and it learns which designs tend to work better for a given task. “The heuristic function improves over time,” says Zhao, “and the search converges to the optimal robot.”

This all happens before the human designer ever picks up a screw.

“This work is a crowning achievement in the a 25-year quest to automatically design the morphology and control of robots,” says Hod Lipson, a mechanical engineer and computer scientist at Columbia University, who was not involved in the project. “The idea of using shape-grammars has been around for a while, but nowhere has this idea been executed as beautifully as in this work. Once we can get machines to design, make and program robots automatically, all bets are off.”

Zhao intends the system as a spark for human creativity. He describes RoboGrammar as a “tool for robot designers to expand the space of robot structures they draw upon.” To show its feasibility, his team plans to build and test some of RoboGrammar’s optimal robots in the real world. Zhao adds that the system could be adapted to pursue robotic goals beyond terrain traversing. And he says RoboGrammar could help populate virtual worlds. “Let’s say in a video game you wanted to generate lots of kinds of robots, without an artist having to create each one,” says Zhao. “RoboGrammar would work for that almost immediately.”

One surprising outcome of the project? “Most designs did end up being four-legged in the end,” says Zhao. Perhaps manual robot designers were right to gravitate toward quadrupeds all along. “Maybe there really is something to it.”